A fact sheet at a glance for handicapping the race.

Learn about all of this year’s Oscar-nominated screenplays and screenwriters in our ten-part series. Click on the titles or pictures to go to the script’s in-depth profile. (Most include links to download the screenplay for free.)

BEST ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY

AMERICAN HUSTLE

Screenwriters: David O. Russell (also director), Eric Warren Singer

Total nominations: 10 (tied for first place), including Best Picture, Director, and all four acting categories

* Russell’s 5th nomination, second for writing; Singer’s first nomination

* Rusell’s 3rd consecutive film to be nominated for Best Picture, Director, and Screenplay

* Singer’s previous credits:

The International

* Script’s original title:

American Bullshit

* Script was on the 2010 Black List

* Highest grossing of all nominated screenplays

Other accolades: BAFTA (Original Screenplay), Golden Globes (Best Picture Comedy), SAG (Cast)

BLUE JASMINE

Screenwriter: Woody Allen (also director)

Modernization of: A Streetcar Named Desire

Total nominations: 3, including Best Actress and Best Supporting Actress

* Allen’s 24th nomination, 16th for writing

Previous wins:

Annie Hall (1978), Best Director and Best Original Screenplay

Hannah and Her Sisters (1987), Best Original Screenplay

Midnight in Paris (2012), Best Original Screenplay

Likelihood of winning: Same as Roman Polanski presenting

DALLAS BUYERS CLUB

Screenwriters: Craig Borten, Melisa Wallack

* Based on a true story

Total nominations: 6, including Best Picture, Best Actor, and Best Supporting Actor

* Borten’s first screenplay written, first screenplay sold, and first produced credit

* Wallack’s first screenplay sold, previous credits include

Mirror Mirror

In development: 20 years

HER

Screenwriter: Spike Jonze

Total nominations: 5, including Best Picture

Other script accolades: Golden Globes, Critics’ Choice, WGA, and more

* Jonze’s fourth feature film, his first solo feature writing credit

Jonze’s other work:

* Nominated for co-writing the song, “The Moon Song”

* Acted in Best Picture nominee

The Wolf of Wall Street

* Produced Best Makeup nominee

Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa

* Previously nominated for directing

Being John Malkovich

* His first two films were nominated for Best Screenplay, both by Charlie Kaufman

* Previously married to Best Original Screenplay winner Sofia Coppola

NEBRASKA

Screenwriter: Bob Nelson

Total nominations: 6, including Best Picture, Director, Actor, Supporting Actress

* First Alexander Payne film not written by Payne

* Fourth of Payne’s last five films nominated for Best Screenplay (his last two won)

* Nelson’s first screenplay

In development: 10 years

* Lowest grossing of all original screenplay nominees

PROJECTED WINNER: Her

Most likely to pull an upset: American Hustle

BEST ADAPTED SCREENPLAY

BEFORE MIDNIGHT

Screenwriters: Richard Linklater (also director), Ethan Hawke (also star), Julie Delpy (also star)

Adapted from: characters from

Before Sunrise by Linklater and Kim Krizan

Total nominations: 1

* Linklater’s and Delpy’s second nomination, Hawke’s third

* All three previously nominated for writing

Before Sunset

* Hawke also nominated for Best Supporting Actor for

Training Day

* Only nominee in category not based on a true story

* Only nominee in category not adapted from a book

* Lowest grossing of all nominated screenplays

Last screenplay nominated that was the third part of a trilogy: Toy Story 3

CAPTAIN PHILLIPS

Screenwriter: Billy Ray

Adapted from: memoir by Richard Phillips with Stephen Talty

Total nominations: 6, including Best Picture and Supporting Actor

Other accolades: WGA Award for Best Adapted Screenplay

* Ray’s first Oscar nomination

Ray’s previous credits: The Hunger Games

Ray’s previous writer-director credits: Shattered Glass,

Breach

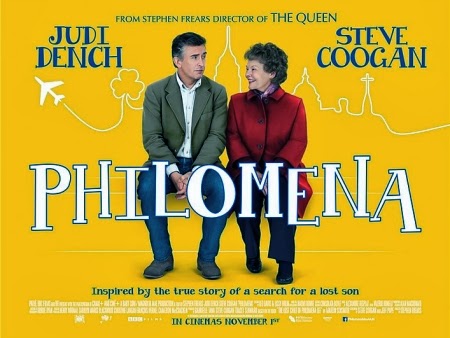

PHILOMENA

Screenwriters: Steve Coogan (also star and producer), Jeff Pope

Adapted from: non-fiction book by Martin Sixsmith

Total nominations: 4, including Best Picture and Best Actress

Other script accolades: BAFTA (Adapted Screenplay)

* 5th Stephen Frears film nominated for its screenplay (

Dangerous Liaisons won)

* Coogan’s 1st feature screenplay

* Coogan’s 1st and 2nd nominations (Best Picture, Best Screenplay)

* Pope’s 1st nomination

12 YEARS A SLAVE

Screenwriter: John Ridley

Adapted from: memoir by Solomon Northrup with David Wilson

Total nominations: 9, including Best Picture, Director, Actor, Supporting Actor, Supporting Actress

Other accolades: Golden Globe (Best Picture Drama), BAFTA (Best

Picture), Critics’ Choice (Best Picture, Adapted Screenplay), Producers

Guild (Best Picture, tied with Gravity)

WGA award: disqualified, Ridley left guild during 2007 strike

*Ridley’s 1st nomination

Ridley’s previous credits: U-Turn,

Undercover Brother,

Red Tails

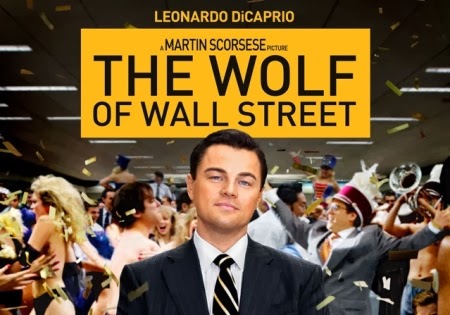

THE WOLF OF WALL STREET

Screenwriter: Terence Winter

Adapted from: memoir by Jordan Belfort

Total nominations: 5, including Best Picture, Director, Actor, Supporting Actor

* Winter’s 1st nomination

* Winter is married to Best Picture nominee Rachel Winter (Dallas Buyers Club)

Winter’s other work: The Sopranos (writer/producer),

Boardwalk Empire (creator)

Number of Scorsese films nominated for Best Screenplay: 8

Number of Scorsese films to win Best Screenplay: 1 (

The Departed)

* Highest grossing of all adapted screenplay nominees

PROJECTED WINNER: 12 Years a Slave

Days Left to Vote in the Inaugural ScripTipps Screenplay Awards: 1 (today)